Flame, a stealthy and complex cyberweapon, was found to be spying on Iran's government officials and computer systems.

NEW

YORK (CNNMoney) -- The "Flame" virus, the most complex computer bug

ever discovered, has been lurking for years inside Iranian government

computers, spying on the country's officials.

Publicly unveiled

this week, the bug is one of the most potent cyber weapons ever spotted

in the wild. Security professionals say it marks a new milestone in the

escalating digital espionage battle.

Flame's complexity and power "exceed[s] those of all other cyber menaces known to date," research firm Kaspersky Lab wrote in a dispatch about its investigation into Flame.

In a statement posted on its website

on Monday, the Iranian National Computer Emergency Response Team (CERT)

said it discovered Flame after "multiple investigations" over the past

few months.

The stealthy malware has been in the wild for at least two years, the CERT team said, evading detection by security software.

It's

a spy bug that's capable of, among other things, capturing what's on a

user's screen, turning on a computer's microphone to record

conversations, detecting who and what is on a network, collecting lists

of vulnerable passwords, and transferring a user's computer files to

another server.

The attack worked. Flame was likely responsible

for recent incidents of "mass data loss" in the government, Iran's CERT

team said in its terse announcement.

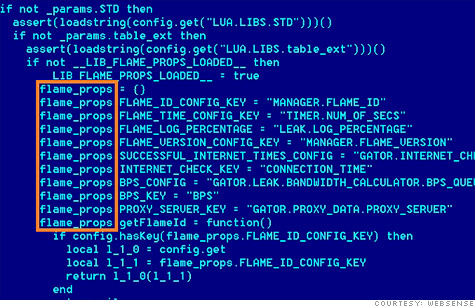

Patrik Runald, director of

research at Websense Security Labs, said Flame is "potentially the most

advanced malware to date, at least in terms of functionality combined

with ability to stay hidden over a long period of time."

Flame is an unusually giant piece of malware: At 20 megabytes, it's about 20 to 30 times larger than typical computer bugs.

Yet

it remained undetected in Iran's government computer systems dating

back to at least 2010, and it was not discovered by any of the 43

antivirus programs the CERT team tested on it.

Now that Flame has

been exposed, Iran is taking defensive measures. Iran's CERT said it

developed a Flame detector over the past few weeks and it is spreading

around a removal tool to rid the government's systems of the virus.

Computer viruses don't stay where you put them, and Iran probably isn't the only victim.

A Hungarian research lab that has been doing its own analysis said it has found traces of the bug

in Europe and the United Arab Emirates. The lab, which began studying

the virus this month, estimates that it may have been active "for as

long as five to eight years."

So if Flame was spying, who was it spying for?

The

Iranian CERT team said it believes there is a "close relation" between

Flame two previous cyber attacks on Iran, known as the Stuxnet and Duqu

computer worms.

"Stuxnet" is a word that sends a shiver of fear through cybersecurity pros.

In an extensive feature on the virus, Vanity Fair calls it

"one of the great technical blockbusters in malware history." The bug

targets "industrial control systems" -- that's jargon for critical

national infrastructure -- and it had the unprecedented ability to

sabotage its target and then cover its tracks.

Stuxnet was used

to attack Iran's nuclear program in 2010. The virus caused centrifuges

in a targeted facility to spin out of control, ultimately destroying it.

A

related bug, Duqu, also targeted Iran's nuclear program. It was

discovered last year and shows evidence of having been developed by

engineers with access to Stuxnet's source code.

Who are those

engineers? The widespread industry belief is that Stuxnet was created by

the United States, Israel, or through the collaboration of both.

"Israel is blessed to be a nation possessing superior technology," Moshe Yaalon, Israel's minister of strategic affairs, said Tuesday in an interview with Israeli Army radio. "In that respect our achievements open up all sorts of opportunities for us."

But

cyber war isn't a one-sided affair. If Flame was a targeted cyber

attack carried out by United States or Israel, the same code could be

reverse-engineered by Iran and sent back our way.

"It's important

to understand that such cyber weapons can easily be used against any

country," Kaspersky said about Flame. "Unlike with conventional warfare,

the more developed countries are actually the most vulnerable in this

case."

This isn't traditional war. The Internet has leveled the playing field, allowing governments that would never launch military attacks on one another to target one another in cyberspace.

"In

warfare, when a bomb goes off it detonates; in cyberwarfare, malware

keeps going and gets proliferated," said Roger Cressey, senior vice

president at security consultancy Booz Allen Hamilton, at a Bloomberg

cybersecurity conference held in New York last month.

"Once a

piece of malware is launched in wild, what happens to that code and its

capability?" he added. "Things like Stuxnet are being

reverse-engineered."

Once it's out there, the code get also get

into the hands of citizens or terrorists with a sophisticated knowledge

of software coding. That's why some cybersecurity advocates are calling

on the U.S. government to better protect itself against an all-out "code war" that some see as inevitable.

"The

terrifying thing is that governments no longer have a monopoly on this

capability," said Tom Kellerman, former commissioner of President

Obama's cyber security council, at the Bloomberg conference. "There is

code out there that puts it in anyone's hands."

No comments:

Post a Comment